Barry Skinstad: Award-winning Documentary Cinematographer and shark specialist

Text by Nicolene Olckers | Images by Barry Skinstad

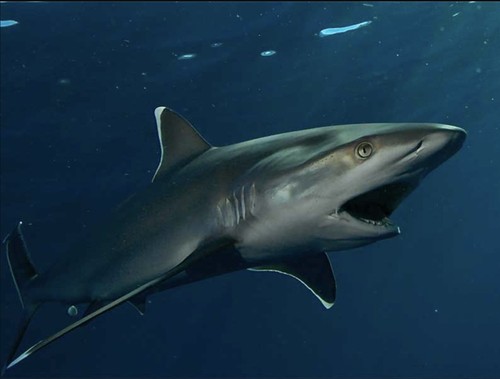

Award-winning documentary Cinema-tographer and shark specialist Barry Skinstad tells us how he became fascinated by these majestic animals.

Growing up in Eshowe, Kwazulu-Natal, not far from the coast, I started diving when I was 13 or 14 and only scuba-dived much later in life. The family dentist in Eshowe, Dr Andrews, was a keen spear fisherman. We would travel either to Sodwana Bay or Cape Vidal to go spearfishing. Having done my military service in the Navy and practised my spearfishing skills while working in Mozambique and Sodwana, I gained more underwater experience.

“My wife, Noleen and I moved to Plettenberg Bay in 2014, said Barry. He was still doing quite a lot of work on the Survivor Series in Fiji. “We run a small farm, and my wife has a livery with a couple of horses. I do as much work in the ocean as I can. I noticed there are many sharks – Great white sharks - that congregate here.” They arrive in the bay during early winter and spend from April until October or November along the Robberg Peninsula. Over the last six years, I tried to do some work with them, diving and filming the sharks that visit the peninsula.

“I also work with the acoustic listening stations around here; several of the tagged Marine animals swim past these listening stations, and these underwater listening stations record them passing by or through the area. I enjoy the whole science side of this and anything to do with Marine sciences.

“The first shark I ever saw on one of those first spearfishing trips with Dr Andrews was a tiger shark. I didn't even know what it was. I told him that I had just seen a shark with stripes. They are distinctive.

My genuine interest in sharks started in Mozambique at the end of 1993 or early 1994.We discovered a dive site called the Pinnacle. In the summer, it is heavy with sharks. We took photographs there at the time, and there were probably 10-14 Zambezi or Bull Sharks in one frame. It was impressive and something special to see. We spent so much time free diving on the Pinnacle and later scuba diving there. We learned a lot about the shark’s behaviour.

I started filming when the Annual Sardine Run was first promoted as a commercial venture. I was with quite a few guys that used to come to Mozambique. They wanted to film sharks and other big marine species. Seeing them diving and thinking: Jeepers!! They can hold the camera and are pretty good photographers, but they have no clue about the marine environment and how to get close to the animals.

Award-winning documentary Cinema-tographer and shark specialist Barry Skinstad tells us how he became fascinated by these majestic animals.

Growing up in Eshowe, Kwazulu-Natal, not far from the coast, I started diving when I was 13 or 14 and only scuba-dived much later in life. The family dentist in Eshowe, Dr Andrews, was a keen spear fisherman. We would travel either to Sodwana Bay or Cape Vidal to go spearfishing. Having done my military service in the Navy and practised my spearfishing skills while working in Mozambique and Sodwana, I gained more underwater experience.

“My wife, Noleen and I moved to Plettenberg Bay in 2014, said Barry. He was still doing quite a lot of work on the Survivor Series in Fiji. “We run a small farm, and my wife has a livery with a couple of horses. I do as much work in the ocean as I can. I noticed there are many sharks – Great white sharks - that congregate here.” They arrive in the bay during early winter and spend from April until October or November along the Robberg Peninsula. Over the last six years, I tried to do some work with them, diving and filming the sharks that visit the peninsula.

“I also work with the acoustic listening stations around here; several of the tagged Marine animals swim past these listening stations, and these underwater listening stations record them passing by or through the area. I enjoy the whole science side of this and anything to do with Marine sciences.

“The first shark I ever saw on one of those first spearfishing trips with Dr Andrews was a tiger shark. I didn't even know what it was. I told him that I had just seen a shark with stripes. They are distinctive.

My genuine interest in sharks started in Mozambique at the end of 1993 or early 1994.We discovered a dive site called the Pinnacle. In the summer, it is heavy with sharks. We took photographs there at the time, and there were probably 10-14 Zambezi or Bull Sharks in one frame. It was impressive and something special to see. We spent so much time free diving on the Pinnacle and later scuba diving there. We learned a lot about the shark’s behaviour.

I started filming when the Annual Sardine Run was first promoted as a commercial venture. I was with quite a few guys that used to come to Mozambique. They wanted to film sharks and other big marine species. Seeing them diving and thinking: Jeepers!! They can hold the camera and are pretty good photographers, but they have no clue about the marine environment and how to get close to the animals.

Operating the camera and working with the animals was much easier because I understood the sharks’ behaviours well. Learning camera skills was easier for me than for somebody to learn animal behaviour in the ocean. That was my advantage.

I landed a job with Earth Touch in 2007 or 2008 and led one of the marine teams for about 7 or 8 years. I travelled up and down the (South) African coast and worldwide—diving and filming natural events, which was great. We filmed most of the annual Sardine Runs, travelled worldwide to Palau, did a lot of work in Mozambique and filmed the Great White Sharks in the Cape. I also filmed Bull sharks (Zambezi’s) and Tiger sharks up in Mozambique, and whale sharks and Manta rays at Mafia Island. Working with a company such as Earth Touch was a considerable advantage (privilege), and moving around the world and witnessing all these fantastic events was a huge advantage (privilege). I have done quite a few films since, with the BBC, NatGeo (National Geographic) and another with Netflix that is about to come out.

The logistics involved are the biggest challenge of working with international film companies. Everything must be entirely above board. Everybody's on the same boat as to what is needed and how we can achieve what we want with the filming. Especially with the white sharks, everybody knows that diving in the Cape is impossible to get in the water every day.

Unlike Mozambique, where the water is clean, you can have good daily visibility. The conditions in the Cape dictate if we will have a three- or four-week window. We will probably be in the water for three to five days in that time frame. It is a barrier, making it more difficult for people to come along and do the same work. Another hurdle is the permits that are needed. These must be in place before filming can commence. The great white sharks are a protected species; you must obtain permits from the necessary authorities, such as the Department of Environmental Affairs, SANParks, or whoever manages the area that you're working in. Obtaining a permit can be problematic, and they do not often issue permits to operate outside a cage. Working with reputable agents to get them takes time and effort and is very expensive.

As a cinematographer, you must have a decent reputation for working with sharks and have produced decent work. You cannot be gung-ho about it, like diving in the water with sharks in harmful conditions. You must know when it is safe to get in the water with them and, at most, be able to sense the shark’s behaviour.

I landed a job with Earth Touch in 2007 or 2008 and led one of the marine teams for about 7 or 8 years. I travelled up and down the (South) African coast and worldwide—diving and filming natural events, which was great. We filmed most of the annual Sardine Runs, travelled worldwide to Palau, did a lot of work in Mozambique and filmed the Great White Sharks in the Cape. I also filmed Bull sharks (Zambezi’s) and Tiger sharks up in Mozambique, and whale sharks and Manta rays at Mafia Island. Working with a company such as Earth Touch was a considerable advantage (privilege), and moving around the world and witnessing all these fantastic events was a huge advantage (privilege). I have done quite a few films since, with the BBC, NatGeo (National Geographic) and another with Netflix that is about to come out.

The logistics involved are the biggest challenge of working with international film companies. Everything must be entirely above board. Everybody's on the same boat as to what is needed and how we can achieve what we want with the filming. Especially with the white sharks, everybody knows that diving in the Cape is impossible to get in the water every day.

Unlike Mozambique, where the water is clean, you can have good daily visibility. The conditions in the Cape dictate if we will have a three- or four-week window. We will probably be in the water for three to five days in that time frame. It is a barrier, making it more difficult for people to come along and do the same work. Another hurdle is the permits that are needed. These must be in place before filming can commence. The great white sharks are a protected species; you must obtain permits from the necessary authorities, such as the Department of Environmental Affairs, SANParks, or whoever manages the area that you're working in. Obtaining a permit can be problematic, and they do not often issue permits to operate outside a cage. Working with reputable agents to get them takes time and effort and is very expensive.

As a cinematographer, you must have a decent reputation for working with sharks and have produced decent work. You cannot be gung-ho about it, like diving in the water with sharks in harmful conditions. You must know when it is safe to get in the water with them and, at most, be able to sense the shark’s behaviour.

We are fortunate to be in the position to do this work and have established a good reputation. We have not had any incidents, and the crews working with us have strict procedures. Decisions are based on observing the animal, when you can see it clearly, and watching its behaviour. Once we determine that the animal/s is relaxed, we only call to get in the water. It's pointless to dive with the animals in dirty conditions. It puts all those involved at risk and is not the wisest thing to do.

I think any exposure to any wild animal is good, especially for the White sharks. They have been under the microscope. These sharks have possibly been responsible for most shocking or fatal shark attacks around the world. To portray them in the right light is very important. I hate it when people emphasise their teeth and the jaws sort of scenario. Unfortunately, that's how these sharks are; they swim around with their teeth exposed and out, unlike other sharks, such as the Zambezi and tiger sharks, in which you'll see their teeth but not as pronounced. I do not try to portray them in a bad light. I am more for describing their beauty and grace in their natural underwater realm. I do not appreciate a gung-ho attitude. When people start riding dorsal fins, pulling the tails or anything like that, it puts the animal and the people at risk.

People are always fascinated by giant animals, whether it's a lion or a big shark. “That is pretty much a general rule throughout the world. Big sharks, big tiger sharks, big great white sharks are very impressive to see underwater, says Barry. “You don't often see those big animals anymore.”

I think I've seen one white shark over 5 meters, and I wasn't in the water, but I've seen a couple of sharks between four and 4 1/2 meters, and even those are impressive. Once you get close to them, you realise their size and the girth of these animals. In their environment, they are in their element. I've managed to get some of the best shots of white sharks. At first, you are somewhat apprehensive and watch them. Once you have been in the water with them and watched them for a while, you always try to get a better shot.

One of the shots I got was of these big white sharks of about four, maybe 4.2 meters, swimming right over our heads. Being underwater and holding your breath while it comes overhead was mind-boggling. I got the images to show. Not in stills but as footage. “It's imposing to see.”

Sharks, as with most underwater animals, can surprise you very quickly. They can switch their behaviours very fast. They become a bit bolder in different conditions. The white sharks in cooler water seem a little more aggressive, as with Ragged Tooth sharks, and it plays a role in their behaviour. With most sharks, you can see the change in how they move. Observing their erratic movements, where and how they hold their pectoral fins, enables you to see if they're a bit more turned on or aggressive than at other times. Temperatures and conditions play a role when working or filming these animals. What always fascinated or interested me more is how quickly they can appear and disappear in the ocean. You can look in an area and look away for half a second, and when you look back, there will be a shark right there. In the water, you must be vigilant and constantly look around you.

I have been involved with two or three of the NatGeo shoots here in Plettenberg Bay and the latest one for BBC Planet Earth III. It was released recently, and we managed to get the opening sequence. It was exciting to see how the seals turned against the sharks. The sharks will only move into the areas where the seals are when they are on the hunt or trying to prey on the seals. More often than not, they will hang around towards the beach, where they seem to be in a kind of limp mode, just moving in and around a space of about 300 or 400 meters. Not go anywhere near the seal colony.

I think any exposure to any wild animal is good, especially for the White sharks. They have been under the microscope. These sharks have possibly been responsible for most shocking or fatal shark attacks around the world. To portray them in the right light is very important. I hate it when people emphasise their teeth and the jaws sort of scenario. Unfortunately, that's how these sharks are; they swim around with their teeth exposed and out, unlike other sharks, such as the Zambezi and tiger sharks, in which you'll see their teeth but not as pronounced. I do not try to portray them in a bad light. I am more for describing their beauty and grace in their natural underwater realm. I do not appreciate a gung-ho attitude. When people start riding dorsal fins, pulling the tails or anything like that, it puts the animal and the people at risk.

People are always fascinated by giant animals, whether it's a lion or a big shark. “That is pretty much a general rule throughout the world. Big sharks, big tiger sharks, big great white sharks are very impressive to see underwater, says Barry. “You don't often see those big animals anymore.”

I think I've seen one white shark over 5 meters, and I wasn't in the water, but I've seen a couple of sharks between four and 4 1/2 meters, and even those are impressive. Once you get close to them, you realise their size and the girth of these animals. In their environment, they are in their element. I've managed to get some of the best shots of white sharks. At first, you are somewhat apprehensive and watch them. Once you have been in the water with them and watched them for a while, you always try to get a better shot.

One of the shots I got was of these big white sharks of about four, maybe 4.2 meters, swimming right over our heads. Being underwater and holding your breath while it comes overhead was mind-boggling. I got the images to show. Not in stills but as footage. “It's imposing to see.”

Sharks, as with most underwater animals, can surprise you very quickly. They can switch their behaviours very fast. They become a bit bolder in different conditions. The white sharks in cooler water seem a little more aggressive, as with Ragged Tooth sharks, and it plays a role in their behaviour. With most sharks, you can see the change in how they move. Observing their erratic movements, where and how they hold their pectoral fins, enables you to see if they're a bit more turned on or aggressive than at other times. Temperatures and conditions play a role when working or filming these animals. What always fascinated or interested me more is how quickly they can appear and disappear in the ocean. You can look in an area and look away for half a second, and when you look back, there will be a shark right there. In the water, you must be vigilant and constantly look around you.

I have been involved with two or three of the NatGeo shoots here in Plettenberg Bay and the latest one for BBC Planet Earth III. It was released recently, and we managed to get the opening sequence. It was exciting to see how the seals turned against the sharks. The sharks will only move into the areas where the seals are when they are on the hunt or trying to prey on the seals. More often than not, they will hang around towards the beach, where they seem to be in a kind of limp mode, just moving in and around a space of about 300 or 400 meters. Not go anywhere near the seal colony.

But when they do go to the colony, as soon as the seals notice them, you see packs of between 20 and 30 seals mobbing the sharks and chasing them out of the area.

It will be nice to think that people's perceptions and awareness of sharks are becoming more in tune with how they are. Rather than seeing them in the JAWS!! Perception. There's been so much exposure, and so many forms made that one would think people would tire of it, but apparently, people love sharks across the board. We have done a couple of Shark Week films as well, and I reckon that Shark Week is probably one of the best TV shows that shows you the fascination for sharks worldwide.

We've done a lot of work with Crocodiles in the Okavango delta; honestly, it's not a fun experience. It is impressive, though. “I would prefer to dive with a shark rather than a crocodile, " jokes Skinstad. Crocodiles are more unpredictable, and the conditions are much more challenging. It's dangerous, and it certainly is much nicer to dive with the sharks.

Producing significant documentaries takes a long time. Not only because of underwater sequences but also because they use sequences from worldwide, stringing them together. I worked on the BBC Planet Earth I for three years, and we would have about four weeks every year to shoot. Ultimately, it is scrunched down to about 8 minutes of footage in the show. That gives you an idea of how much footage you would need to produce a section or a segment. Regarding the Shark Week shows, you will probably spend a week and a half of actual filming. If you get good conditions, both topside and underwater footage, it will be quickly cut into a 52-minute documentary. It depends on the production.

This year thus far has been quiet. It usually only starts picking up around the end of January or February, and I'm sure one or two Shark Week shows will come up.

On my diving Wishlist, I'd like to go and dive with the Humpback Whales in a place like Tonga. I haven't done that in clean water, though I have done a lot of work with humpback whales, but not in crystal-clean water. They usually move pretty quickly. Any significant events are always a great attraction to see and document. It is nice to document some of these events and share them with millions worldwide.

It will be nice to think that people's perceptions and awareness of sharks are becoming more in tune with how they are. Rather than seeing them in the JAWS!! Perception. There's been so much exposure, and so many forms made that one would think people would tire of it, but apparently, people love sharks across the board. We have done a couple of Shark Week films as well, and I reckon that Shark Week is probably one of the best TV shows that shows you the fascination for sharks worldwide.

We've done a lot of work with Crocodiles in the Okavango delta; honestly, it's not a fun experience. It is impressive, though. “I would prefer to dive with a shark rather than a crocodile, " jokes Skinstad. Crocodiles are more unpredictable, and the conditions are much more challenging. It's dangerous, and it certainly is much nicer to dive with the sharks.

Producing significant documentaries takes a long time. Not only because of underwater sequences but also because they use sequences from worldwide, stringing them together. I worked on the BBC Planet Earth I for three years, and we would have about four weeks every year to shoot. Ultimately, it is scrunched down to about 8 minutes of footage in the show. That gives you an idea of how much footage you would need to produce a section or a segment. Regarding the Shark Week shows, you will probably spend a week and a half of actual filming. If you get good conditions, both topside and underwater footage, it will be quickly cut into a 52-minute documentary. It depends on the production.

This year thus far has been quiet. It usually only starts picking up around the end of January or February, and I'm sure one or two Shark Week shows will come up.

On my diving Wishlist, I'd like to go and dive with the Humpback Whales in a place like Tonga. I haven't done that in clean water, though I have done a lot of work with humpback whales, but not in crystal-clean water. They usually move pretty quickly. Any significant events are always a great attraction to see and document. It is nice to document some of these events and share them with millions worldwide.

Categories

2025

2024

February

March

April

May

October

My name is Rosanne… DAN was there for me?My name is Pam… DAN was there for me?My name is Nadia… DAN was there for me?My name is Morgan… DAN was there for me?My name is Mark… DAN was there for me?My name is Julika… DAN was there for me?My name is James Lewis… DAN was there for me?My name is Jack… DAN was there for me?My name is Mrs. Du Toit… DAN was there for me?My name is Sean… DAN was there for me?My name is Clayton… DAN was there for me?My name is Claire… DAN was there for me?My name is Lauren… DAN was there for me?My name is Amos… DAN was there for me?My name is Kelly… DAN was there for me?Get to Know DAN Instructor: Mauro JijeGet to know DAN Instructor: Sinda da GraçaGet to know DAN Instructor: JP BarnardGet to know DAN instructor: Gregory DriesselGet to know DAN instructor Trainer: Christo van JaarsveldGet to Know DAN Instructor: Beto Vambiane

November

Get to know DAN Instructor: Dylan BowlesGet to know DAN instructor: Ryan CapazorioGet to know DAN Instructor: Tyrone LubbeGet to know DAN Instructor: Caitlyn MonahanScience Saves SharksSafety AngelsDiving Anilao with Adam SokolskiUnderstanding Dive Equipment RegulationsDiving With A PFOUnderwater NavigationFinding My PassionDiving Deep with DSLRDebunking Freediving MythsImmersion Pulmonary OedemaSwimmer's EarMEMBER PROFILE: RAY DALIOAdventure Auntie: Yvette OosthuizenClean Our OceansWhat to Look for in a Dive Boat

2023

January

March

Terrific Freedive ModeKaboom!....The Big Oxygen Safety IssueScuba Nudi ClothingThe Benefits of Being BaldDive into Freedive InstructionCape Marine Research and Diver DevelopmentThe Inhaca Ocean Alliance.“LIGHTS, Film, Action!”Demo DiversSpecial Forces DiverWhat Dive Computers Don\'t Know | PART 2Toughing It Out Is Dangerous

April