The Edge of Extinction

Text and photos by Kim Steinhardt

Can sea otters survive the human threat?

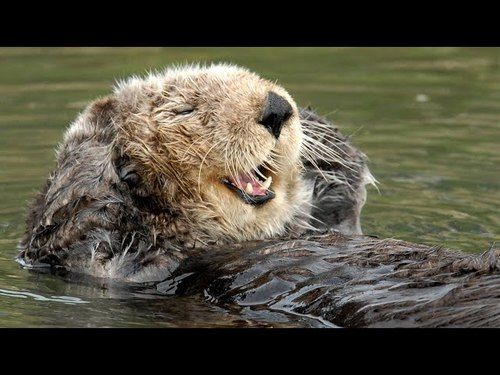

I WAS HOOKED THE FIRST TIME I saw a southern sea otter bobbing in the surf off the coast of California’s Big Sur. I didn’t know then that I would be as spellbound by these rare creatures decades later as I was at that very first sighting. And little did I know that I was witnessing the latest act in a continuing saga of survival against all odds and an all too real human threat.

I was 15 years old and had just returned from an extraordinary trip to the British Virgin Islands, where I spent most of an entire month in the water. Alongside my teenage cousin, I lived in the crystal-blue watery world, whether it was our daily snorkeling over wonderfully undisturbed reefs or diving around the RMS Rhone, a mysterious 100-year-old wreck off Salt Island. The day a hurricane swept through was the only one we did not spend in the water. Even then, we were sorely tempted to go diving while the brief calm of the hurricane’s eye crossed over.

When I returned to my California home, I spent as much time as possible continuing to discover the wonders at the ocean’s edge. Unlike the Caribbean, the central California coast’s cold waters limited my exploration to the shoreline, so I had to adjust my viewing perspective. That’s how I discovered sea otters.

Sea otters are much more than just another pretty face. They are known as an indicator or sentinel species because what happens to sea otters reveals much about the conditions of the nearshore ocean waters in which they live, often foreshadowing changes that affect humans and our relationship with the ocean.

I now realize the creature I saw as a teen was one of the small number of southern sea otters then remaining on the planet. I didn’t know they were in a halting recovery from near extinction and that at one point only about 50 remained in California. It was just a rare, curious, and thrilling sight.

Since then I have also come to understand much more about the role humans have played in their plight. Unfortunately, human activity still threatens the southern sea otter or California sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis). They’ve been here before — at a crossroads, with extinction on one path and survival on the other.

Can sea otters survive the human threat?

I WAS HOOKED THE FIRST TIME I saw a southern sea otter bobbing in the surf off the coast of California’s Big Sur. I didn’t know then that I would be as spellbound by these rare creatures decades later as I was at that very first sighting. And little did I know that I was witnessing the latest act in a continuing saga of survival against all odds and an all too real human threat.

I was 15 years old and had just returned from an extraordinary trip to the British Virgin Islands, where I spent most of an entire month in the water. Alongside my teenage cousin, I lived in the crystal-blue watery world, whether it was our daily snorkeling over wonderfully undisturbed reefs or diving around the RMS Rhone, a mysterious 100-year-old wreck off Salt Island. The day a hurricane swept through was the only one we did not spend in the water. Even then, we were sorely tempted to go diving while the brief calm of the hurricane’s eye crossed over.

When I returned to my California home, I spent as much time as possible continuing to discover the wonders at the ocean’s edge. Unlike the Caribbean, the central California coast’s cold waters limited my exploration to the shoreline, so I had to adjust my viewing perspective. That’s how I discovered sea otters.

Sea otters are much more than just another pretty face. They are known as an indicator or sentinel species because what happens to sea otters reveals much about the conditions of the nearshore ocean waters in which they live, often foreshadowing changes that affect humans and our relationship with the ocean.

I now realize the creature I saw as a teen was one of the small number of southern sea otters then remaining on the planet. I didn’t know they were in a halting recovery from near extinction and that at one point only about 50 remained in California. It was just a rare, curious, and thrilling sight.

Since then I have also come to understand much more about the role humans have played in their plight. Unfortunately, human activity still threatens the southern sea otter or California sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis). They’ve been here before — at a crossroads, with extinction on one path and survival on the other.

Southern sea otter pups learn how to eat shellfish by mimicking their mothers’ actions, but this pup was floating while holding an empty shell.

The Pacific Rim Fur Trade

The earliest threat to the sea otter came from the commercial fur trade. Sea otters were valued for their pelts, which could be transformed into luxurious fur coats, hats, and other clothes. Because their fur is the densest of any creature on the planet, their pelts were considered superior to all other fur.

When the broad commercial trade began in the 1700s, the geographic range of the sea otter (including three subspecies: southern, northern, and Asian) stretched north from Japan, around the Pacific Rim, across what is now the Bering Strait, and down the U.S. West Coast as far south as Baja California. Although Russian fur traders pioneered commercial hunting and trade, American, British, and, to a lesser extent, other European traders soon joined.

In the mid-1700s, sea otters still thrived in the waters along the Pacific coast, but hunting sea otters was not an easy business. The long seafaring voyages were difficult, dangerous, and expensive. Crews sought to load their ships with as many pelts as possible to make the voyage worthwhile.

The earliest threat to the sea otter came from the commercial fur trade. Sea otters were valued for their pelts, which could be transformed into luxurious fur coats, hats, and other clothes. Because their fur is the densest of any creature on the planet, their pelts were considered superior to all other fur.

When the broad commercial trade began in the 1700s, the geographic range of the sea otter (including three subspecies: southern, northern, and Asian) stretched north from Japan, around the Pacific Rim, across what is now the Bering Strait, and down the U.S. West Coast as far south as Baja California. Although Russian fur traders pioneered commercial hunting and trade, American, British, and, to a lesser extent, other European traders soon joined.

In the mid-1700s, sea otters still thrived in the waters along the Pacific coast, but hunting sea otters was not an easy business. The long seafaring voyages were difficult, dangerous, and expensive. Crews sought to load their ships with as many pelts as possible to make the voyage worthwhile.

The treacherous nearshore ocean waters off the rugged coastline of Big Sur made hunting sea otters difficult and may have contributed to their survival.

A great commercial sea otter hunting frenzy was in full swing, but this was not a sustainable hunt. There were no limits on the number of animals killed or when hunters could take them. Otters were slaughtered without regard to whether they were male or female, adult, subadult, or moms and pups. Traders did not consider what we now know are considerable negative impacts of removing sea otters from coastal ecosystems in which they serve as a keystone, or especially impactful, species. Sea otters play a vital role, for example, in controlling sea urchin populations to maintain healthy kelp forests, which are home to a variety of sea life.

As otter hunts moved south along the California coast, the dwindling numbers made it increasingly difficult to have commercially successful voyages. By the end of the 19th century, traders had killed hundreds of thousands of sea otters for their pelts, leaving perhaps fewer than 2,000 remaining. With so few surviving into the early 1900s, there were not enough sea otters left to make commercial trade worthwhile. In 1911, with the entire species nearing extinction, sea otters finally received legal protection under the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention agreement between the U.S., Russia, Japan, and Great Britain.

Too Little, Too Late?

The treaty protected sea otters and other furred marine mammals. By the time it was adopted, however, sea otters were already widely believed to be extinct.

In a curious twist of fate, a small colony of southern sea otters survived near Big Sur. A handful of locals knew of their existence but carefully protected that secret until the late 1930s. This secrecy allowed the sea otters to begin their recovery unimpeded by further direct human interaction. They became public again only when the stretch of Highway 1 along the Big Sur coast first opened to traffic in 1938.

When I saw my first sea otter, I would have been shocked to learn that they had been rediscovered off the Big Sur coastline less than 30 years before. This tiny population was a remnant of their formerly robust numbers and range. Yet the entire current population of roughly 3,000 southern sea otters owes its existence to that tiny group.

The southern sea otters’ recovery has stalled for several years. Researchers have found that although sea otters have a healthy reproductive rate, they have likely reached the carrying capacity of the narrow ecosystem where they live. After hunting reduced their historical range, the remaining several hundred miles of central California’s coast cannot support the food needs of any significantly greater number of sea otters. The annual sea otter census for 2022 will give us an indication of whether any temporary increases in food supply result in a greater number of sea otters.

As otter hunts moved south along the California coast, the dwindling numbers made it increasingly difficult to have commercially successful voyages. By the end of the 19th century, traders had killed hundreds of thousands of sea otters for their pelts, leaving perhaps fewer than 2,000 remaining. With so few surviving into the early 1900s, there were not enough sea otters left to make commercial trade worthwhile. In 1911, with the entire species nearing extinction, sea otters finally received legal protection under the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention agreement between the U.S., Russia, Japan, and Great Britain.

Too Little, Too Late?

The treaty protected sea otters and other furred marine mammals. By the time it was adopted, however, sea otters were already widely believed to be extinct.

In a curious twist of fate, a small colony of southern sea otters survived near Big Sur. A handful of locals knew of their existence but carefully protected that secret until the late 1930s. This secrecy allowed the sea otters to begin their recovery unimpeded by further direct human interaction. They became public again only when the stretch of Highway 1 along the Big Sur coast first opened to traffic in 1938.

When I saw my first sea otter, I would have been shocked to learn that they had been rediscovered off the Big Sur coastline less than 30 years before. This tiny population was a remnant of their formerly robust numbers and range. Yet the entire current population of roughly 3,000 southern sea otters owes its existence to that tiny group.

The southern sea otters’ recovery has stalled for several years. Researchers have found that although sea otters have a healthy reproductive rate, they have likely reached the carrying capacity of the narrow ecosystem where they live. After hunting reduced their historical range, the remaining several hundred miles of central California’s coast cannot support the food needs of any significantly greater number of sea otters. The annual sea otter census for 2022 will give us an indication of whether any temporary increases in food supply result in a greater number of sea otters.

Life for the southern sea otter is often perilous, as shown in this deadly fight between a territorial male and a young challenger.

A Human Obstacle Course

The sea otters’ food supply consists of many shellfish and marine invertebrates. Sea otters are among the few mammals that use tools; they crack open shellfish using rocks they gather and carry on their chests. Their food and caloric requirements are extraordinarily high due to the high metabolic rate they maintain to stay warm in the cold ocean waters. They do not have a thick, insulating layer of blubber like other marine mammals but rely solely on their rich fur for warmth. Sea otters must consume 20 to 30 percent of their body weight each day to survive. The need for such high caloric intake makes them especially vulnerable to pollution and toxic chemicals, some of which concentrate in shellfish and become more deadly by the time they are consumed.

To enlarge their population, southern sea otters need to increase the amount of available food by expanding their geographic territory farther back into their historic range. Again, there is a human threat to their well-being. By eating shellfish, humans compete for the sea otters’ limited food supply. Commercial fishing also limits abalone and sea urchin availability. These reductions in available food, in turn, constrain the sea otter population.

Expansion of the range is important to push back against another human threat to their long-term survival: oil spills. Given its small, several-hundred-mile area and the potential impact of a major oil spill, the entire southern sea otter population is in danger from even one significant accident. In 1989 the Exxon Valdez oil spill off the Alaskan coastline killed around 40 percent of the sea otter population in Prince William Sound along with countless other marine mammals, fish, and wildlife. The risk to the southern sea otter is very real today, given the millions of gallons of Alaskan crude oil transported by tanker along the California coast.

An additional existential threat the southern sea otter faces comes from climate change, with the impact of human growth and development on the Earth. The many and increasing effects of the warming planet, changing oceans, and fluctuations in sea levels have serious consequences, some of which affect the sea otter. It is understood, for example, that warming temperatures at the ocean’s surface level leads to increased acidification. Shellfish have calcium-carbonate-based shells, which are quite sensitive to that level, and any increase makes it harder to grow and maintain healthy shells. Any impact on the health and number of shellfish, as sea otters’ primary prey, translates into a potential impact on sea otters already constrained by a limited food supply.

One Pup at a Time

Due to these threats and the static population numbers, survival of the sea otter now comes down to repopulation, adding one pup at a time. The need to grow their numbers has never been clearer, yet the obstacles are daunting. In the face of this pressure, the special sea otter mom and pup relationship is key to their success in the future.

In addition to feeding pups for many months, sea otter moms must teach the pups how to swim, dive, hunt, eat, and groom their fur. They must be constantly vigilant to protect the vulnerable pups from various threats. These tasks can be so taxing that late in weaning, or once the pup is fully weaned, some mothers die because they have severely depleted their own resources.

The federal Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act as well as various state laws protect southern sea otters. These protections are critical to their continued recovery. But protections don’t succeed in a vacuum. It takes good science, sound policymaking, and strong citizen involvement to achieve long-term success in recovering any species on the edge of extinction. Citizen vigilance is required to ensure these protections survive evolving threats and shifting political winds.

On the Edge

After gradually learning more about sea otters, I now view the creatures as both incredibly resilient and incredibly vulnerable. Their strength is most apparent in their uncanny ability to survive in turbulent and dangerous ocean waters. Otters must routinely weather the punishing natural forces of storms, dynamic tides, seasonal changes in the kelp forests, ups and downs in the food supply, and threats from other marine species such as great white sharks. They have had the incredible resilience to withstand — to this point — the human impacts that alter the ocean environment, whether from climate change, hunting, oil drilling, overharvesting of fisheries, deadly nets, or competition for food.

Yet sea otters are particularly vulnerable to these threats precisely because they are dependent on the ocean and all that it brings. Their future is not guaranteed. In that way, they are quite like humans, and I see us in them. We, too, are completely dependent on the ocean and our environment for our survival. We are just as vulnerable.

I still see hope when I look at the long-term saga of the sea otters’ rugged fight for survival, even with today’s perilously low otter population. I’m optimistic about the long-term survival of both our species, so long as we remain committed to making the types of changes required to preserve our ocean habitat. When I see the wonder of the sea otters, I hope and imagine that 50 years from now people will look back and say that we were good stewards of the ocean and all creatures that depend upon it. AD

The sea otters’ food supply consists of many shellfish and marine invertebrates. Sea otters are among the few mammals that use tools; they crack open shellfish using rocks they gather and carry on their chests. Their food and caloric requirements are extraordinarily high due to the high metabolic rate they maintain to stay warm in the cold ocean waters. They do not have a thick, insulating layer of blubber like other marine mammals but rely solely on their rich fur for warmth. Sea otters must consume 20 to 30 percent of their body weight each day to survive. The need for such high caloric intake makes them especially vulnerable to pollution and toxic chemicals, some of which concentrate in shellfish and become more deadly by the time they are consumed.

To enlarge their population, southern sea otters need to increase the amount of available food by expanding their geographic territory farther back into their historic range. Again, there is a human threat to their well-being. By eating shellfish, humans compete for the sea otters’ limited food supply. Commercial fishing also limits abalone and sea urchin availability. These reductions in available food, in turn, constrain the sea otter population.

Expansion of the range is important to push back against another human threat to their long-term survival: oil spills. Given its small, several-hundred-mile area and the potential impact of a major oil spill, the entire southern sea otter population is in danger from even one significant accident. In 1989 the Exxon Valdez oil spill off the Alaskan coastline killed around 40 percent of the sea otter population in Prince William Sound along with countless other marine mammals, fish, and wildlife. The risk to the southern sea otter is very real today, given the millions of gallons of Alaskan crude oil transported by tanker along the California coast.

An additional existential threat the southern sea otter faces comes from climate change, with the impact of human growth and development on the Earth. The many and increasing effects of the warming planet, changing oceans, and fluctuations in sea levels have serious consequences, some of which affect the sea otter. It is understood, for example, that warming temperatures at the ocean’s surface level leads to increased acidification. Shellfish have calcium-carbonate-based shells, which are quite sensitive to that level, and any increase makes it harder to grow and maintain healthy shells. Any impact on the health and number of shellfish, as sea otters’ primary prey, translates into a potential impact on sea otters already constrained by a limited food supply.

One Pup at a Time

Due to these threats and the static population numbers, survival of the sea otter now comes down to repopulation, adding one pup at a time. The need to grow their numbers has never been clearer, yet the obstacles are daunting. In the face of this pressure, the special sea otter mom and pup relationship is key to their success in the future.

In addition to feeding pups for many months, sea otter moms must teach the pups how to swim, dive, hunt, eat, and groom their fur. They must be constantly vigilant to protect the vulnerable pups from various threats. These tasks can be so taxing that late in weaning, or once the pup is fully weaned, some mothers die because they have severely depleted their own resources.

The federal Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act as well as various state laws protect southern sea otters. These protections are critical to their continued recovery. But protections don’t succeed in a vacuum. It takes good science, sound policymaking, and strong citizen involvement to achieve long-term success in recovering any species on the edge of extinction. Citizen vigilance is required to ensure these protections survive evolving threats and shifting political winds.

On the Edge

After gradually learning more about sea otters, I now view the creatures as both incredibly resilient and incredibly vulnerable. Their strength is most apparent in their uncanny ability to survive in turbulent and dangerous ocean waters. Otters must routinely weather the punishing natural forces of storms, dynamic tides, seasonal changes in the kelp forests, ups and downs in the food supply, and threats from other marine species such as great white sharks. They have had the incredible resilience to withstand — to this point — the human impacts that alter the ocean environment, whether from climate change, hunting, oil drilling, overharvesting of fisheries, deadly nets, or competition for food.

Yet sea otters are particularly vulnerable to these threats precisely because they are dependent on the ocean and all that it brings. Their future is not guaranteed. In that way, they are quite like humans, and I see us in them. We, too, are completely dependent on the ocean and our environment for our survival. We are just as vulnerable.

I still see hope when I look at the long-term saga of the sea otters’ rugged fight for survival, even with today’s perilously low otter population. I’m optimistic about the long-term survival of both our species, so long as we remain committed to making the types of changes required to preserve our ocean habitat. When I see the wonder of the sea otters, I hope and imagine that 50 years from now people will look back and say that we were good stewards of the ocean and all creatures that depend upon it. AD

Posted in Alert Diver Fall Editions, Research, Underwater Conservation

Posted in Southern Sea Otters, Otters, Big Sur, Fur rade, Extinction

Posted in Southern Sea Otters, Otters, Big Sur, Fur rade, Extinction

Categories

2025

2024

February

March

April

May

October

My name is Rosanne… DAN was there for me?My name is Pam… DAN was there for me?My name is Nadia… DAN was there for me?My name is Morgan… DAN was there for me?My name is Mark… DAN was there for me?My name is Julika… DAN was there for me?My name is James Lewis… DAN was there for me?My name is Jack… DAN was there for me?My name is Mrs. Du Toit… DAN was there for me?My name is Sean… DAN was there for me?My name is Clayton… DAN was there for me?My name is Claire… DAN was there for me?My name is Lauren… DAN was there for me?My name is Amos… DAN was there for me?My name is Kelly… DAN was there for me?Get to Know DAN Instructor: Mauro JijeGet to know DAN Instructor: Sinda da GraçaGet to know DAN Instructor: JP BarnardGet to know DAN instructor: Gregory DriesselGet to know DAN instructor Trainer: Christo van JaarsveldGet to Know DAN Instructor: Beto Vambiane

November

Get to know DAN Instructor: Dylan BowlesGet to know DAN instructor: Ryan CapazorioGet to know DAN Instructor: Tyrone LubbeGet to know DAN Instructor: Caitlyn MonahanScience Saves SharksSafety AngelsDiving Anilao with Adam SokolskiUnderstanding Dive Equipment RegulationsDiving With A PFOUnderwater NavigationFinding My PassionDiving Deep with DSLRDebunking Freediving MythsImmersion Pulmonary OedemaSwimmer's EarMEMBER PROFILE: RAY DALIOAdventure Auntie: Yvette OosthuizenClean Our OceansWhat to Look for in a Dive Boat

2023

January

March

Terrific Freedive ModeKaboom!....The Big Oxygen Safety IssueScuba Nudi ClothingThe Benefits of Being BaldDive into Freedive InstructionCape Marine Research and Diver DevelopmentThe Inhaca Ocean Alliance.“LIGHTS, Film, Action!”Demo DiversSpecial Forces DiverWhat Dive Computers Don\'t Know | PART 2Toughing It Out Is Dangerous

April