Cannabis & Diving

Cannabis/ marijuana has been known to man for thousands of years. It is believed to have originated in central Asia some 12,000 years ago and that it was widely used by Neolithic times for its protein-rich seeds, oils and fibers. [1] Some of the earliest reports of its use date back to approximately 4000 BC, when it was actively farmed and considered one of the “five grains” in China.[2]

Likewise, it was commonly used by the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa for many centuries – long before Europeans set foot on the continent. The more common and “proudly South African” name (“dagga”) is actually a Khoi-derived word, which means “intoxication”. In the year of his arrival (1652), Jan van Riebeeck already documented that dagga was used in South Africa. We know that centuries ago, dagga was widely used for a variety of medical conditions. Dr Russell Reynolds (the personal physician of Queen Victoria) published his experiences in using cannabis for a range of conditions and Queen Victoria allegedly used it to ease menstrual pain.

Likewise, it was commonly used by the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa for many centuries – long before Europeans set foot on the continent. The more common and “proudly South African” name (“dagga”) is actually a Khoi-derived word, which means “intoxication”. In the year of his arrival (1652), Jan van Riebeeck already documented that dagga was used in South Africa. We know that centuries ago, dagga was widely used for a variety of medical conditions. Dr Russell Reynolds (the personal physician of Queen Victoria) published his experiences in using cannabis for a range of conditions and Queen Victoria allegedly used it to ease menstrual pain.

Figure 1: The heading of the publication of Dr Reynolds in 1890[3]

In South Africa, dagga was also accepted into general use by the Dutch settlers and even traded by the Dutch East India Company. However, its use was later banned in the 1920’s. Now, almost exactly 100 years later, the personal and private use of dagga was legalized in South Africa on 18 September 2018 via a ruling of the Constitutional Court.[4] Today, dagga is not legalised in South Africa, but also in a number of other countries in the world. Now that its use has been legalised, DANSA has received some enquiries regarding the safety of diving in the context of dagga (and cannabidiol (CBD) oil) use.

When considering CBD oil in isolation, the short (but possibly incorrect) answer to the safety question is that it has no effect, since CBD is not psychoactive and it would therefore unlikely affect diving safety. However, not all formulations of CBD are “pure” and some may contain delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is psychoactive. THC is metabolised (forming more than 100 metabolites), of which some (like hydroxyl-THC) are also psychoactive.[5]

Similar to diving while under the influence of alcohol, diving while under the influence of THC and related substances would be risky. Extrapolation from the risks of motor vehicle accidents after using dagga provides some useful information and guidance. Tests indicate that cannabis use results in deficient tracking, attention, reaction time, short-term memory, hand-eye coordination, vigilance, time perception, distance perception, decision making and concentration.[6] Therefore, cannabis intoxication during a dive will alter perception of the environment and impair both cognitive and psychomotor performance.[7] Nonetheless, it is well known that many divers are using cannabis (although there is a paucity of data concerning diving while under the influence). A survey of recreational divers in the United Kingdom revealed that (of the 479 divers who responded), 22% of the divers (a total of 105) reported using illicit drugs since they first learned to dive, and 94% of them had used cannabis.[8] However, as mentioned, it is unclear how many of these divers were “under the influence” while diving. There are however a few reports that affected divers in warm water became lethargic and even fell asleep when submerged, and divers in cold water found that tolerance to cold was reduced to one-fifth of the limit.[9] This is therefore not an issue to be ignored by the safety-conscious in the diving community.

Whether you are a dive operator trying to ensure safety of the operation, or a CBD or dagga user (for recreational or medical purposes) trying to ensure your own safety while diving, testing for the psychoactive effects (to determine whether someone is “under the influence”) is actually quite difficult in the recreational diving setting. Unfortunately, the current urine tests for cannabis do not distinguish between the psychoactive and non-psychoactive metabolites – it only tests “positive for cannabinoids”. While this was a sufficient test in the recent past (when cannabis use was still illegal), it has become more important now to distinguish between the psychoactive and non-psychoactive substances in order to identify to which extent one is affected at the time. For this reason, the previous advice regarding waiting periods for a few weeks (to “totally clear the body of all metabolites”)[10,11] is not an adequate approach any longer and it can now even be considered a violation of an individual’s rights if such (overly) strict rules are applied. Any “zero-tolerance” policies should thus be applied to the active metabolites and not the non-active metabolites that could remain in the body for weeks. The same argument would hold for commercial diving operations where tests for cannabis (as part of wider drug screening) are performed. This then explains the main difference between testing for cannabis use and alcohol use in the context of diving (where “zero tolerance policies” are applied to both): The breathalyser tests for alcohol actually detects the active ingredient, while urine tests for cannabis also detects non-active metabolites.

The screening test that currently works best to detect whether someone is “under the influence” is a saliva test, since it tests for the actual psychoactive substance (THC). However, the best test we currently have available in South Africa has a lower detection limit of 40ng/mL (while recommended limits for detecting intoxication is 4ng/mL on screening tests and 2ng/mL for confirmatory tests[12] – thus a ten-to-twenty-fold difference!). It is also still quite expensive. For this reason, mass testing of “everyone” is not really an effective way to currently screen whether someone is affected or not. However, if someone tests positive, one can be sure that they are quite affected at that time. An operator could then refuse participation as a result of a safety risk. Such intoxication could also be considered illegal (pending further court cases to confirm), because cannabis use is only legal in the private context (and not in public).

If you are using CBD oil and want to make sure you are safe while diving, one can look at the labelling of the oil for purity and confirmation that there is no THC contamination. However, not all manufacturers would declare “contaminants” – particularly if present in low concentrations. Therefore, there is (at this stage) no reliable way of confirming whether one is affected without some significant expense.

Another way of determining safety is to consider the half-life of THC in the body, since it is actually relatively short. If it is possible to observe a sufficient time-delay between using CBD oil, “smoking a joint” or eating a dagga cookie and diving, one can reasonably ensure that it is safe to dive. Unfortunately, we do not have specific values available for the oil, but there are studies (with graphs) that looked at smoking and ingestion of dagga.

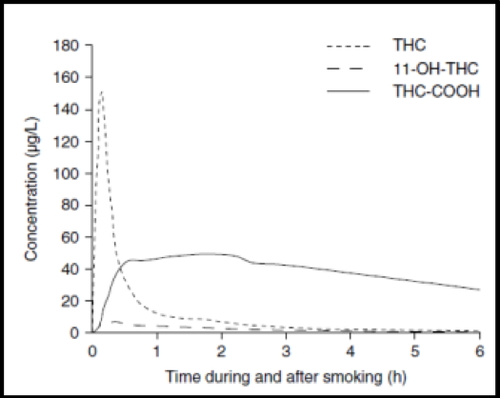

THC levels drop quite rapidly after smoking cannabis and the levels are low enough for “normal functioning” within about 2 to 3 hours – (the dotted line in the graph below represents THC concentration). Driving tests have also indicated that impairment is dose-dependent and generally lasts for 2 to 4 hours.[6,13] Notice again that the non-psychoactive metabolite (THC-COOH) remains detectable in the blood for a long period – much longer than the psychoactive substance and psychoactive effects, which proves the point that urine tests would not indicate whether one is inebriated or not.

In South Africa, dagga was also accepted into general use by the Dutch settlers and even traded by the Dutch East India Company. However, its use was later banned in the 1920’s. Now, almost exactly 100 years later, the personal and private use of dagga was legalized in South Africa on 18 September 2018 via a ruling of the Constitutional Court.[4] Today, dagga is not legalised in South Africa, but also in a number of other countries in the world. Now that its use has been legalised, DANSA has received some enquiries regarding the safety of diving in the context of dagga (and cannabidiol (CBD) oil) use.

When considering CBD oil in isolation, the short (but possibly incorrect) answer to the safety question is that it has no effect, since CBD is not psychoactive and it would therefore unlikely affect diving safety. However, not all formulations of CBD are “pure” and some may contain delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is psychoactive. THC is metabolised (forming more than 100 metabolites), of which some (like hydroxyl-THC) are also psychoactive.[5]

Similar to diving while under the influence of alcohol, diving while under the influence of THC and related substances would be risky. Extrapolation from the risks of motor vehicle accidents after using dagga provides some useful information and guidance. Tests indicate that cannabis use results in deficient tracking, attention, reaction time, short-term memory, hand-eye coordination, vigilance, time perception, distance perception, decision making and concentration.[6] Therefore, cannabis intoxication during a dive will alter perception of the environment and impair both cognitive and psychomotor performance.[7] Nonetheless, it is well known that many divers are using cannabis (although there is a paucity of data concerning diving while under the influence). A survey of recreational divers in the United Kingdom revealed that (of the 479 divers who responded), 22% of the divers (a total of 105) reported using illicit drugs since they first learned to dive, and 94% of them had used cannabis.[8] However, as mentioned, it is unclear how many of these divers were “under the influence” while diving. There are however a few reports that affected divers in warm water became lethargic and even fell asleep when submerged, and divers in cold water found that tolerance to cold was reduced to one-fifth of the limit.[9] This is therefore not an issue to be ignored by the safety-conscious in the diving community.

Whether you are a dive operator trying to ensure safety of the operation, or a CBD or dagga user (for recreational or medical purposes) trying to ensure your own safety while diving, testing for the psychoactive effects (to determine whether someone is “under the influence”) is actually quite difficult in the recreational diving setting. Unfortunately, the current urine tests for cannabis do not distinguish between the psychoactive and non-psychoactive metabolites – it only tests “positive for cannabinoids”. While this was a sufficient test in the recent past (when cannabis use was still illegal), it has become more important now to distinguish between the psychoactive and non-psychoactive substances in order to identify to which extent one is affected at the time. For this reason, the previous advice regarding waiting periods for a few weeks (to “totally clear the body of all metabolites”)[10,11] is not an adequate approach any longer and it can now even be considered a violation of an individual’s rights if such (overly) strict rules are applied. Any “zero-tolerance” policies should thus be applied to the active metabolites and not the non-active metabolites that could remain in the body for weeks. The same argument would hold for commercial diving operations where tests for cannabis (as part of wider drug screening) are performed. This then explains the main difference between testing for cannabis use and alcohol use in the context of diving (where “zero tolerance policies” are applied to both): The breathalyser tests for alcohol actually detects the active ingredient, while urine tests for cannabis also detects non-active metabolites.

The screening test that currently works best to detect whether someone is “under the influence” is a saliva test, since it tests for the actual psychoactive substance (THC). However, the best test we currently have available in South Africa has a lower detection limit of 40ng/mL (while recommended limits for detecting intoxication is 4ng/mL on screening tests and 2ng/mL for confirmatory tests[12] – thus a ten-to-twenty-fold difference!). It is also still quite expensive. For this reason, mass testing of “everyone” is not really an effective way to currently screen whether someone is affected or not. However, if someone tests positive, one can be sure that they are quite affected at that time. An operator could then refuse participation as a result of a safety risk. Such intoxication could also be considered illegal (pending further court cases to confirm), because cannabis use is only legal in the private context (and not in public).

If you are using CBD oil and want to make sure you are safe while diving, one can look at the labelling of the oil for purity and confirmation that there is no THC contamination. However, not all manufacturers would declare “contaminants” – particularly if present in low concentrations. Therefore, there is (at this stage) no reliable way of confirming whether one is affected without some significant expense.

Another way of determining safety is to consider the half-life of THC in the body, since it is actually relatively short. If it is possible to observe a sufficient time-delay between using CBD oil, “smoking a joint” or eating a dagga cookie and diving, one can reasonably ensure that it is safe to dive. Unfortunately, we do not have specific values available for the oil, but there are studies (with graphs) that looked at smoking and ingestion of dagga.

THC levels drop quite rapidly after smoking cannabis and the levels are low enough for “normal functioning” within about 2 to 3 hours – (the dotted line in the graph below represents THC concentration). Driving tests have also indicated that impairment is dose-dependent and generally lasts for 2 to 4 hours.[6,13] Notice again that the non-psychoactive metabolite (THC-COOH) remains detectable in the blood for a long period – much longer than the psychoactive substance and psychoactive effects, which proves the point that urine tests would not indicate whether one is inebriated or not.

Figure 2: Mean plasma concentrations of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 11-hydroxy-TCH (11-OH-THC) and 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC (THC-COOH) of six subjects during and after smoking a cannabis cigarette containing about 34mg of THC[14]

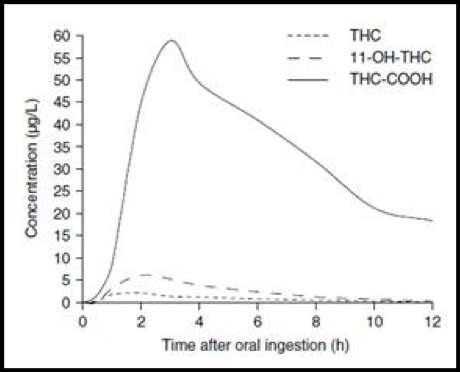

With ingestion of dagga, there is a lower peak, but the half-life is longer (four to six hours). It should however be noted that the plasma levels differs between people ingesting the same amount of cannabis.

With ingestion of dagga, there is a lower peak, but the half-life is longer (four to six hours). It should however be noted that the plasma levels differs between people ingesting the same amount of cannabis.

Figure 3: Mean plasma concentrations of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 11-hydroxy-THC (11-OH-THC) and 11-nor-9-carboxy THC (THC-COOH) of six cancer patients after ingestion of one oral dose of 15mg[5]

Since the psychoactive effects would be the main acute safety concern during diving, it is advisable that divers stay out of the water for at least 6 to 8 hours following ingestion of “dagga cookies” or the oil (just in case there is any THC in the oil), so that they are confident there would be no psychoactive effects. This period should obviously be extended if a large amount was ingested.

Because of the legalisation of dagga and the fact that this would pose some difficulty for employers who need to ensure health and safety at work, it is expected that better saliva testing equipment would become available and it would be more affordable to perform screening tests in future.

For more information on the fascinating history of dagga in South Africa, readers are encouraged to visit the Wikipedia site.[15] Divers are reminded that this article only considers the intoxicating effect of dagga. Fitness-to-dive evaluations in the context of dagga-use should however consider some of the longer-term effects of use too, including the effects on the lungs as a result of smoking, etc. Any concerns regarding fitness should be discussed with a diving medical physician.

References

Since the psychoactive effects would be the main acute safety concern during diving, it is advisable that divers stay out of the water for at least 6 to 8 hours following ingestion of “dagga cookies” or the oil (just in case there is any THC in the oil), so that they are confident there would be no psychoactive effects. This period should obviously be extended if a large amount was ingested.

Because of the legalisation of dagga and the fact that this would pose some difficulty for employers who need to ensure health and safety at work, it is expected that better saliva testing equipment would become available and it would be more affordable to perform screening tests in future.

For more information on the fascinating history of dagga in South Africa, readers are encouraged to visit the Wikipedia site.[15] Divers are reminded that this article only considers the intoxicating effect of dagga. Fitness-to-dive evaluations in the context of dagga-use should however consider some of the longer-term effects of use too, including the effects on the lungs as a result of smoking, etc. Any concerns regarding fitness should be discussed with a diving medical physician.

References

- https://www.niceguysdelivery.com/blog/globalmedicalcannabisuse (Accessed 24 March 2019)

- https://www.visualcapitalist.com/history-medical-cannabis-shown-one-giant-map (Accessed 24 March 2019)

- Reynolds JR. On the therapeutical uses and toxic effects of cannabis indica. Lancet. 1890;135(3473):637-638

- http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2018/30.pdf (Accessed 24 March 2019)

- Grotenhermen F. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(4):327-360

- Kelly E, Darke S, Ross J, A review of drug use and driving: epidemiology, impairment, risk factors and risk perceptions, Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004;23(3):319–344

- Pace T, Mifsud J, Cali-Corleo R, Fenech AG, Ellul-Micallef R. Medication, Recreational Drugs and Diving. Malta Med J. 2005;17(1):9-15

- Dowse MS, Shaw S, Cridge C, Smerdon G. The use of drugs by UK recreational divers: illicit drugs. Diving Hyperb Med. 2011 Mar; 41(1):9-15

- Groner-Strauss W, Strauss MB. Divers face special peril in use/abuse of drugs. Phys Sports Med. 1976;4(12):30-36

- Viders H. Marijuana and Diving. Alert Diver Online. 2016; 3. Available from http://www.alertdiver.com/Marijuana_and_Diving (Accessed 24 March 2019)

- Divers Alert Network. Marijuana and Fitness to Dive: The Experts’ Opinion. 2017;3. Available from https://alertdiver.eu/en_US/articles/marijuana-and-fitness-to-dive-the-experts-opinion (Accessed 24 March 2019)

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Federal register 2015;80(94):28054-28077. Available from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2015-05-15/pdf/2015-11523.pdf (Accessed 24 March 2019)

- Ramaekers JG, Berghaus G, Van Laar GM, Drummer OH. Dose related risk of motor vehicle crashes after cannabis use, Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73(2):109–119

- Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. Blood cannabinoids: I. absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. J Anal Toxicol. 1992;16(5):276-282

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cannabis_in_South_Africa. (Accessed 24 March 2019)

Categories

2025

2024

February

March

April

May

October

My name is Rosanne… DAN was there for me?My name is Pam… DAN was there for me?My name is Nadia… DAN was there for me?My name is Morgan… DAN was there for me?My name is Mark… DAN was there for me?My name is Julika… DAN was there for me?My name is James Lewis… DAN was there for me?My name is Jack… DAN was there for me?My name is Mrs. Du Toit… DAN was there for me?My name is Sean… DAN was there for me?My name is Clayton… DAN was there for me?My name is Claire… DAN was there for me?My name is Lauren… DAN was there for me?My name is Amos… DAN was there for me?My name is Kelly… DAN was there for me?Get to Know DAN Instructor: Mauro JijeGet to know DAN Instructor: Sinda da GraçaGet to know DAN Instructor: JP BarnardGet to know DAN instructor: Gregory DriesselGet to know DAN instructor Trainer: Christo van JaarsveldGet to Know DAN Instructor: Beto Vambiane

November

Get to know DAN Instructor: Dylan BowlesGet to know DAN instructor: Ryan CapazorioGet to know DAN Instructor: Tyrone LubbeGet to know DAN Instructor: Caitlyn MonahanScience Saves SharksSafety AngelsDiving Anilao with Adam SokolskiUnderstanding Dive Equipment RegulationsDiving With A PFOUnderwater NavigationFinding My PassionDiving Deep with DSLRDebunking Freediving MythsImmersion Pulmonary OedemaSwimmer's EarMEMBER PROFILE: RAY DALIOAdventure Auntie: Yvette OosthuizenClean Our OceansWhat to Look for in a Dive Boat

2023

January

March

Terrific Freedive ModeKaboom!....The Big Oxygen Safety IssueScuba Nudi ClothingThe Benefits of Being BaldDive into Freedive InstructionCape Marine Research and Diver DevelopmentThe Inhaca Ocean Alliance.“LIGHTS, Film, Action!”Demo DiversSpecial Forces DiverWhat Dive Computers Don\'t Know | PART 2Toughing It Out Is Dangerous

April